Anatolian Rock Revival

An interview with Ertu from Turkey. Part of the Listening to Listeners series from sometime in 2019.

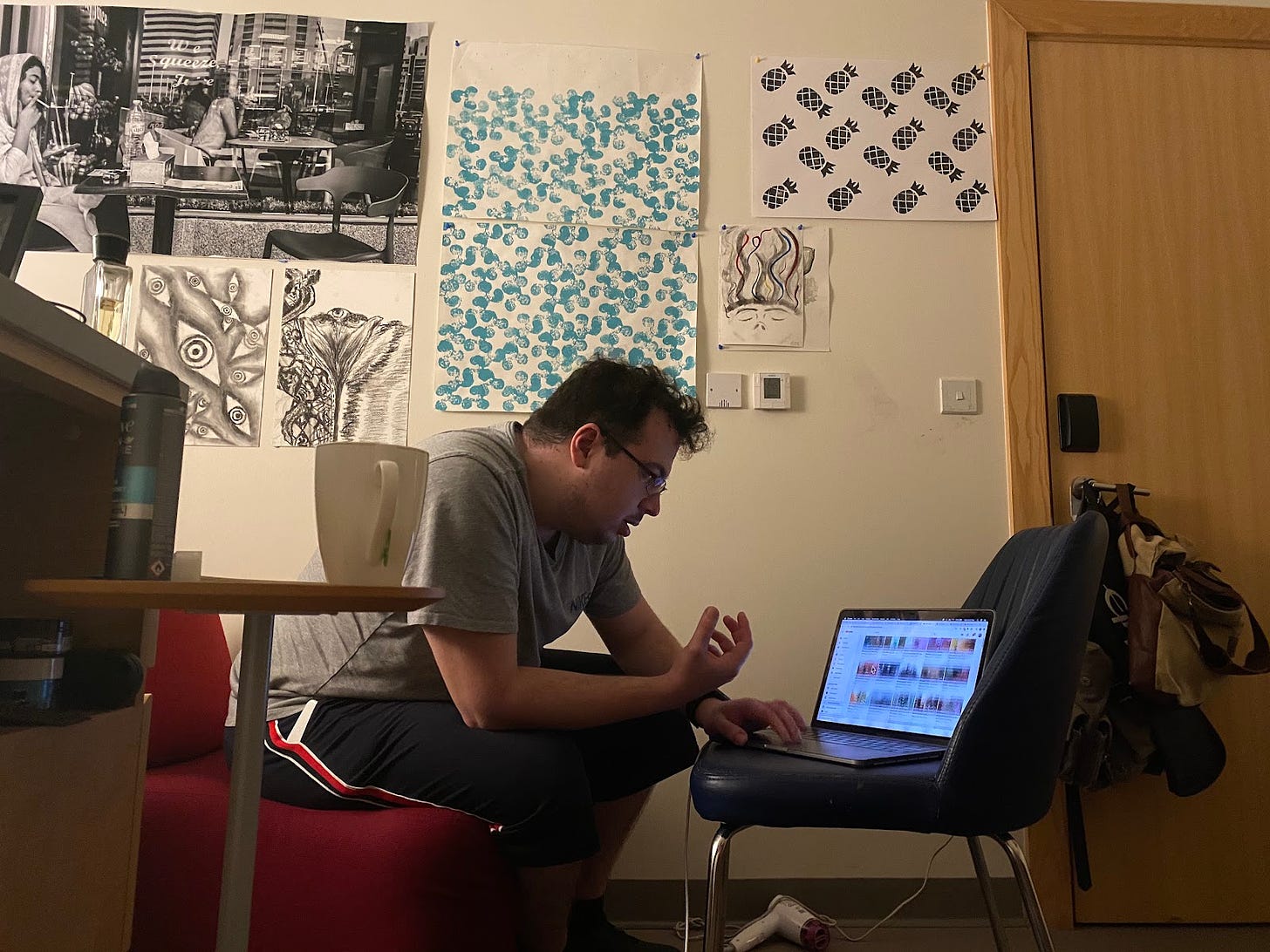

Ertunga Sarisözen, fondly called Ertu, came up to my bedroom on a late Wednesday night to listen to music. We’d graduated from university last week, but we still remained on campus; like aliens in our hometown. Our mutual friend recently took a repatriation flight back home and we were having an informal get-together, to help her pack up the past four years of her life. My phone was connected to the speaker and the 1966 track, Kara Kaşlı Haticem, started playing. Ertu was in disbelief when he realized that I knew this type of music.

The conversation that followed from the midst of that packing-frenzy turned into a proper sit-down listening session over green tea, cigarettes, and warm lights. I talked about how I came across the Anatolian Rock Revival Project (ARRP) early last year as the endpoint of crate digging into two separate genres. I was first introduced to the genre by watching clips of Altin Gün, a contemporary Anatolian rock band performing at the NYU Abu Dhabi Arts Center in the Spring of 2019. This discovery also coincided with my interest in finding psychedelic variations of classical rock. After discovering Zamrock from Zambia, YouTube recommendations and Reddit forums led me to the Anatolian Rock Revival Project.

As we opened the ARRP YouTube page, Ertu confessed how he’d been remarkably moved by the project. A non-profit project dedicated to bringing non-mainstream pieces from the Turkish Rock History into light through partnerships with graphic artists and illustrators, ARRP is an interdisciplinary, archival project. From 7 inches to early dubplates, ARRP converts these half-century-old recordings into YouTube uploads complemented by highly accurate and relevant visual art commissions they provide using local Turkish talent.

From the expansive repertoire of almost 150 songs and growing, Ertu’s first choice for the evening was a track titled ‘Gurbet’ by Özdemir Erdoğan. The name of the song means “the state of being away from home”; a state that had become all too familiar to the both of us, with the pandemic leaving us to stay back on a deserted campus two weeks after graduation. Gurbet more specifically refers to the state of being an expatriate, separated from the homeland. “When you think about the South Asian expats here; the cab drivers, helpers at restaurants, they’re here so they can save up and provide for their families back at home”, Ertu added. While this is one angle to understand the feeling of gurbet, the story narrated by Erdoğan introduces a different socio-political landscape as Ertu went on to explain.

“Migration to Germany peaked in the ’70s and started in the ’60s. There were just a lot of opportunities in Germany to become factory workers and still earn decent money, save, and be able to come back to Turkey and have a decent life… just like with South Asians here [in the UAE] factories were being set up in Germany and they wanted cheap labor, and Turkey was able to provide that labor.” While the song’s illustration depicts this context using the colors of the German flag, the silhouette of a migrant captures the literary reality that the song’s lyrics try to paint.

“I have a problem, I don’t know who to talk to; maybe the clouds. I have the wound of gurbet, because I have been away. Clouds in the sky, give me some news from my beloved.”

Although Ertu no longer has to look up at the clouds to read about the stories of Anatolia (as in the chorus of this song), the essence of gurbet still strikes a deep, personal chord with his own reality.

“At first, I used to listen to this song whenever I used to feel homesick, because that’s what this song is about, lyrically. When I think about my family back home, I miss them a lot, and I listen.”

But the meaning sometimes seeps over and takes on a life beyond lyrics.

“Very recent example, last semester in New York, I was with a high-school friend of mine. He was one of my roommates from boarding school and had found his way to New York. We used to have these nights where we would have some Turkish food and drink some Raki, and especially with this drink from home, you would get very emotional and homesick. Imagine this, two Turkish dudes, missing home, missing family and friends, in the middle of New York City, enjoying Turkish food and alcohol in the right mood, with this song in the background and just being in the moment and trying to hopefully think about the future while also thinking about the past with nostalgia; it’s interesting.”

“It talks about the emotional hardship of being an ex-pat. That begs the question, “Okay, why are you doing that?”. Well, why am I doing that? For my future. I am here because I am investing in my future, I am investing in the future of my family as well. Otherwise, I would just be back home with my family.“

I could feel a strong, visceral connection with Ertu’s narrative of how a 20-something-year-old Turkish student in the Emirates identified with the story of a migrant trash-picker in Germany the ‘60s. He believes that this emotional response comes from the sheer timelessness of Anatolian rock lyrics. “When you look at it, Anatolian rock, you will see many examples of folk music being translated into rock. Not all Anatolian rock is folk but you will see a lot of examples of that, because of how these lyrics tell a story or problem that everyone can connect or relate to easily.”

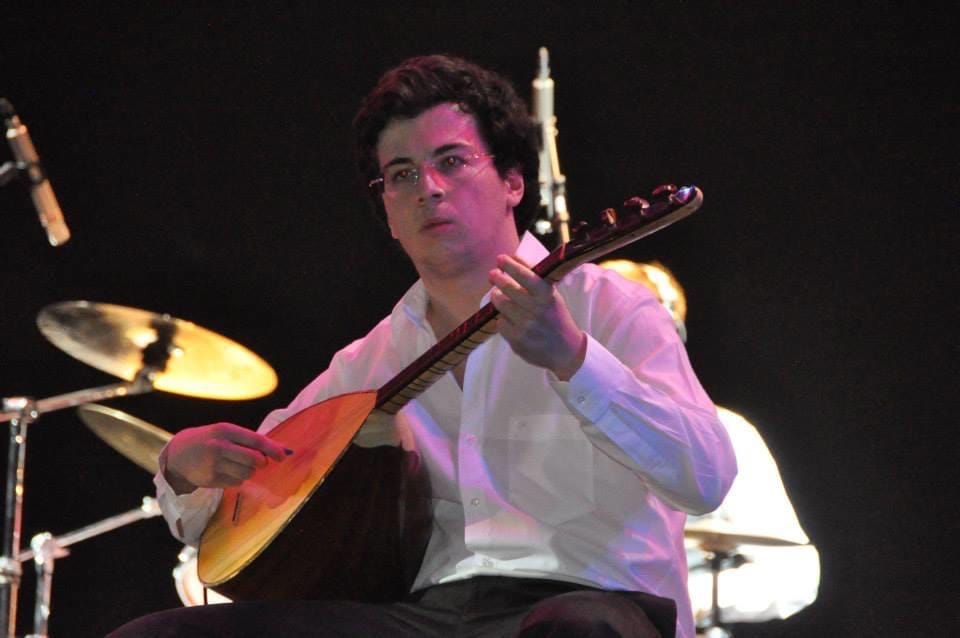

As we started to discuss how Anatolian rock revival paved the way for Anatolian folk revival, Ertu opened a new tab on my computer to substantiate his intuitive argument. Yet another song by Özdemir Erdoğan, although he admittedly prefers the rendering of another artist, this song is a rock interpretation of what he called “the most famous Turkish folk song”. Titled ‘Uzun İnce Bir Yoldayım’, it literally translates to “I am on a long thin road”. Originally rendered by Âşık Veysel, a blind man who plays the indigenous string-instrument Bağlama, the folk song is usually interpreted as “a metaphor for life. Your destiny is set and you are on this road. You don’t know where it ends, but it is set”.

After briefly listening to Veysel’s original, Ertu chose to listen to a cover of the song by Cem Karaca and Barış Manço. Seminal figures of Anatolian music history, “Barış, rock artist who’s been out of Turkey a lot, touring Asian countries like Japan, Korea, and performing his songs over there. Trying to spread the love for Turkish culture through their music. Cem makes rock originals across 3-4 rock bands, but other songs are traditional poems that he turned into songs”. He admits that this ‘translatory process’ is “a very common, distinctive theme in Anatolian Rock music”.

Almost as common and distinctive as the human tendency to politicize folklore and folk music. Anatolian rock was no exception. “The politicization of art started before the ’60s but it culminated into a peak in the ’80s. On 12 September 1980, there was a coup d’etat in Turkey. It was such a time in Turkey, where a brother would kill another brother. The same family. Because one of them would be leftist and another rightist. The country was going towards a civil war. Cem, the rockstar, was the symbol of the leftist movement.”

“It was the time when 3 or 4 of Cem’s songs were banned because of the political state the country was in … he has a lot of songs where he is criticizing the system. Pushing for a more leftist Turkey.” As Ertu mentioned earlier, the ease with which the public could relate to Anatolian rock, both due to its widespread appeal and lyrical relatability, led to fierce political contention to control the meaning-making systems behind the genre.

Ertu described the song’s lyrics to be full of “metaphors. The moment that I came to earth, I was put on this pressure of life. You know, the social, cultural, economic, political pressures and how in life you always need to keep going right?”. Typically, I assumed that this meant that the conservative right-wing government resorted to censorship to control artists and how they made music that reinterpreted folk stories of these contemporary dilemmas.

“That doesn’t happen in Turkey actually. You know what, Turkish people, I can easily generalize and say, when it comes to art, I think people respect it no matter what kind of message it has or what kind of roots it has. A piece of music, a painting, a play, whatever it is, Turkish people have the utmost respect for artists and people who devote their life to art.” Even though the government banned Cem’s music at one point, Ertu added that “I wouldn’t imagine a conservative being not happy with this folk music being Westernized in Anatolian rock. In fact, they would be happier. “See this is our music and now it can be played using western instruments as well”. From the other side of the story, the conservative side, Anatolian rock actually helps promote the culture”.

From this angle, Anatolian rock music gave the opportunity for artists, both Turkish and others, to swap the Bağlama for a 6-string Stratocaster and the percussion of Davul for a 5-piece Tama Superstar drum kit. Despite the western embellishments, the core of these songs remains authentic, for the lack of a better word. Through its strong foundations in folk reinterpretation, the genre provides an artistic narrative to contextualize the social, political, and cultural histories of Ertu’s transcontinental home. In many ways, writing about Ertu’s experience as a listener provides a template for appreciating traditionalism without nationalism; a means to appreciate indigenous art outside of cultural analysis and domination. Sometimes music needs to be politicized, Westernized, reoriented. But sometimes it’s just music. Thanks for listening, Ertu.